Back on Stage!

On Sunday, I did my one-man show, The Accidental Hero, for the first time since COVID. It was a pre-season game, a tune-up for a string of gigs in May. I wondered, do I still have it? Does the show still have an audience? Happy to say, yes and yes. Here are thoughts and observations.

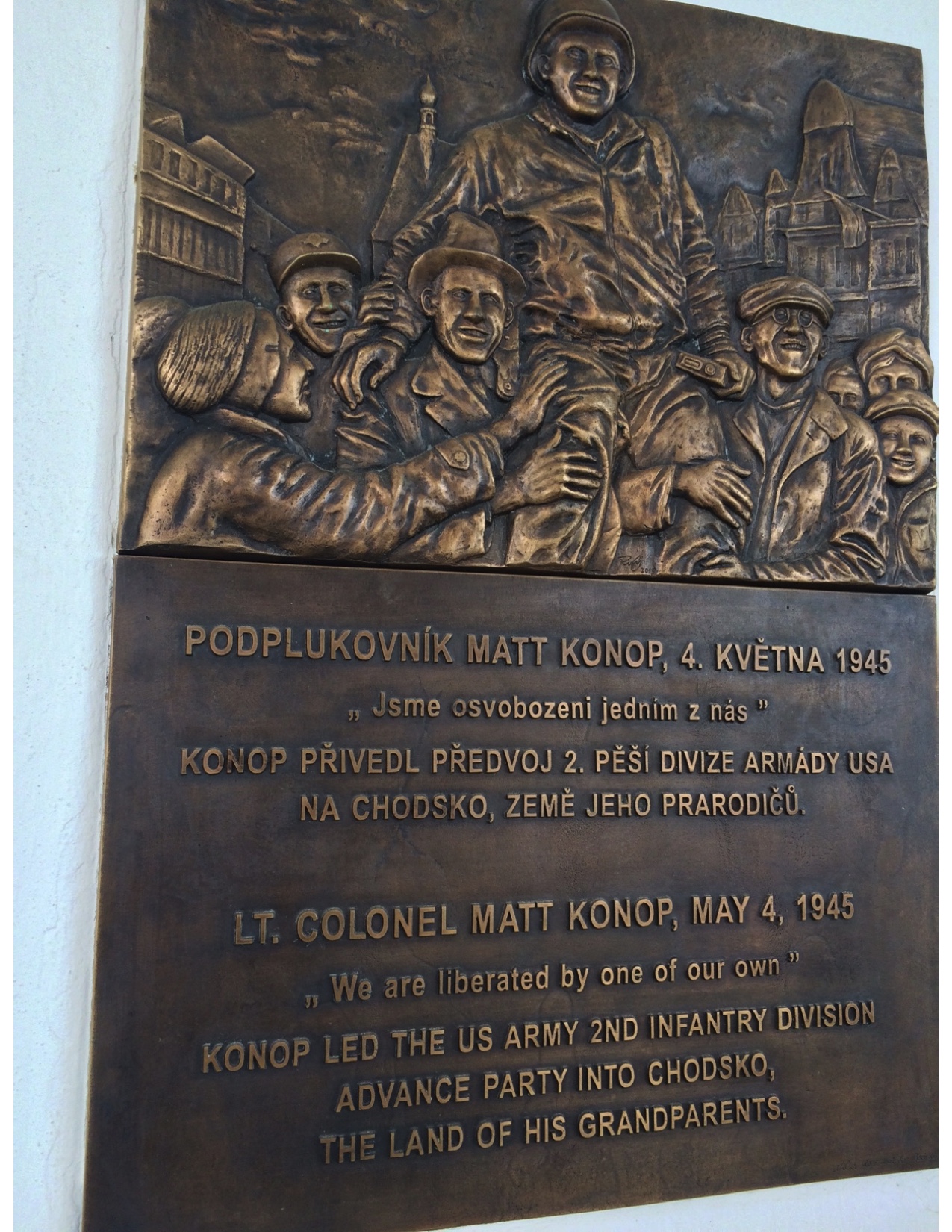

Ukraine has changed everything. Not since Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and Poland has Europe experienced an unprovoked attack of this magnitude. After my show on Sunday, several people wanted to talk about Ukraine, and asked me questions about WWII and Russia’s invasion. My show features the US Army liberation of the Czechs from the Nazis, and how awful 41 years of post-war Soviet/Russian domination was for the Czechs. My grandfather helped liberate the Czechs in 1945, but then could only watch as the Moscow-backed Communist Party seized power in a coup and eliminated Czech freedoms. When grandpa died in 1983, the Czechs still were not free.

In 2014 when I did the show in Domazlice, Czech Republic for the first time, Russia had just invaded the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. Every Czech speaker at Domazlice’s annual WWII liberation ceremony mentioned Crimea. I knew about the Russian invasion, but it didn’t dawn on me until I was on stage for the ceremony that Russia’s unprovoked aggression was also an existential threat to my Czech friends. Russia had claimed they were only safeguarding the ethnic Russians in Crimea, the same lie Hitler used to justify grabbing the Sudetenland portion of Czechoslovakia in 1938. So of course, my Czech friends believed Putin’s intentions went well beyond Crimea. They were correct, as we’ve seen since February 24 of this year. While Russian military planners and many in the West were surprised by the Ukrainians’ fierce resistance in the current conflict, it makes sense in view of Ukraine’s tortured history under the Russians. The Ukrainians know exactly what is at stake: their very existence. They are fighting for survival.

Domazlice, Czech Republic on May 5, 2104. Every Czech speaker that day invoked the invasion of Crimea. US Army WWII veterans Herman Geist and Robert Gilbert seated in foreground in front of Mayor Miroslav Mach. I was seated next to Herman Geist when I snapped this photo. Herman turned 97 last week and I will see him and his wife Barbara in Domazlice in a few weeks. He served in my grandfather’s division.

My American audience on Sunday was fascinated, and perhaps a bit horrified, by these parallels. When I bring the show to the Czech Republic in a few weeks, the audience will not have the luxury of being thousands of miles from the war. Indeed, the town of Domazlice, population 11,000, has already welcomed over 100 Ukrainian refugees.

My show benefited from the COVID hiatus. I didn’t publicize Sunday’s performance because I wasn’t sure if I’d be ready for prime time. How rusty would it be? A few days before the show, my wife and I had coffee with a pianist friend and his spouse. The piano player told me was he bringing a piece back into his repertoire. His teacher, who lives in Sweden and works with him over zoom, predicted he would perform the music better than he had a few years ago. She said he would experience it fresh and would play with greater range and subtly. I said to him, “Henry, I hope that happens with my show on Sunday!” And it did.

The last time I did the show was in Cincinnati on a Sunday at 1 pm. As the show started on Omaha Beach, I noticed the theater sound system was louder than what I recalled from the tech load-in. The sound effects kept getting louder and the building shook with battle noise. Then two fighter jets roared over the theater on their way to a Cincinnati Bengals pro football game flyover a mile away. Had a stage manager cued the pilots, it couldn’t have been timed more perfectly for my show. I didn’t realize it at the time, but those jets were my send-off. And now it’s great to be back.

The show connects. I’m always amazed how my grandfather’s story opens a channel for people to tell me their stories. For instance, I’m writing this blog in a library and a woman just said she was at Sunday’s show and told me about her father’s WWII service. Her name is Mary and her dad was a sergeant in a medic unit during the Battle of the Bulge. She said when I rattled off the stats from that battle (19,000 Americans killed, 47,000 wounded) it reminded her of a story her father told her. In the bitter cold of the battle, he stayed up all night with his hand on the belly of a wounded German soldier, comforting him and tending to his injury. Then dawn came and the young man passed away.

Several people from our condo complex (we downsized during COVID) have stopped me in the hallway or on a sidewalk to talk about the show and ask where I’m doing it next. And they usually have a story to tell. In fact, a neighbor down the hall told me his older brother was in a tank crew in the Battle of the Bulge.

I love to perform it. I missed the show for the first months of the pandemic, but then like so many other things during COVID I just got used to not having it. In fact, I had forgotten how absolutely thrilling it is to do it. I am grateful my grandfather’s story fell into my lap, and so many people have helped me bring it to audiences across the country and overseas. Anytime I do it, I bring my A+ Game. Guaranteed. It’s such a treat to do it again. My gratitude is why I’m back to writing blogs, and will be shooting video. Stay tuned!

Next Gigs:

May 3-8 Czech Tour and Sister Cities Delegation (Two Rivers, Wisconsin – Domazlice, Czech Republic)

May 14 Glenville, Minnesota, Bohemian Brick Hall, 1 pm and 3:30 pm

May 23 Arlington Heights, Illinois, Metropolis Performing Arts Center, 7:30 pm

Domazlice, Czech Republic, May 5, 2015. US Ambassador to the Czech Republic, Andrew Schapiro, standing in front of US Army WWII veterans Robert Gilbert, Herman Geist, and James Duncan. All three are Honorary Citizens of Domazlice, as is my grandfather, Matt Konop.